As spring arrives, the waters and beaches of the mid-Atlantic and Gulf coasts will begin filling with spawning horseshoe crabs (Limulus polyphemus), a species which has called the planet home for over 200 million years.

During the late spring and early summer, adult horseshoe crabs travel from deep ocean waters to beaches along the East and Gulf coasts to breed. Once the females come to shore to meet the waiting males, they release natural chemicals called pheromones, sending a signal that it’s time to mate. The males grasp onto the females and together they head to the shoreline.

On the beach, the females dig small nests and deposit eggs, then the males fertilize the eggs. The process can be repeated multiple times with tens of thousands of eggs laid each season.

Horseshoe crab eggs provide a vital food source at a major migratory stopover site along the Atlantic Flyway, allowing migrating birds to refuel before the next leg of their journey. In the Delaware Bay region, where horseshoe crabs are a critical species, their eggs serve as a vital food source for species like the rufa red knot. In fact, drastic population declines for the red knot in the 90’s were directly attributed to overharvesting of horseshoe crabs.

Responsible Offshore Wind Energy Development

Across the Northeast and Mid-Atlantic, where offshore wind energy is an exciting option for states to meet both climate goals and a rising demand for affordable, reliable energy, NWF advocates for the protection of important species like horseshoe crabs at every stage of offshore wind development and energy production.

While offshore wind energy development presents potential risks to wildlife, experts agree those risks can be significantly reduced through responsible siting, robust mitigation measures, and ongoing environmental monitoring.

Below are just a few of the measures NWF has supported to protect horseshoe crabs and other seafloor species throughout the offshore wind process.

Prioritizing the Carl N. Shuster Horseshoe Crab Reserve

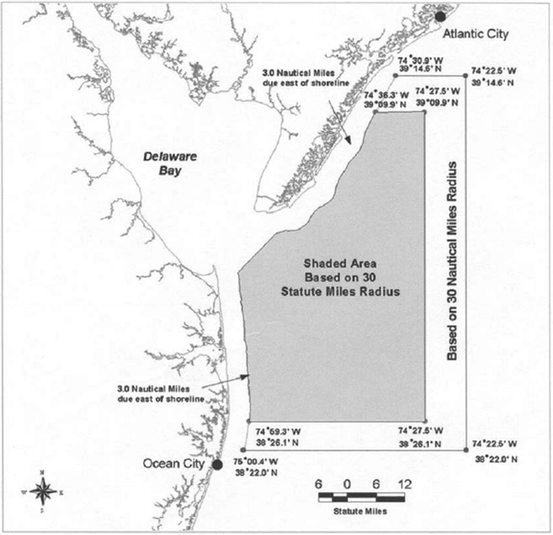

During the site selection process for offshore wind in the waters between Atlantic City, New Jersey and Ocean City, Maryland, NWF and partners advocated for the exclusion of the Carl N. Shuster Horseshoe Crab Reserve (established in 2001) off the mouth of the Delaware Bay (figure right).

The Carl N. Shuster reserve is about 30 nm in radius, located in federal waters, and is closed to commercial horseshoe crab harvest except for limited biomedical collection.

The reserve protects overwintering adult and sub-adult horseshoe crabs from harvest. The National Wildlife Federation encouraged the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM) to exclude coastal and seafloor habitats that are designated for horseshoe crab spawning from energy siting.

Another project off the coast of Delaware and Maryland which chose to avoid construction activities on beaches during horseshoe crab spawning, also conducted a site-specific study on potential electromagnetic field (EMF) impacts to horseshoe crabs and found that the electric field produced would be below the detection thresholds of most marine organisms. Additionally, projects bury cables wherever feasible in order to reduce EMF impacts as a required mitigation measure.

For more information on EMF and offshore wind, check out our fact sheet here!

General Protection for Seafloor Species

Beyond their importance to horseshoe crabs, seafloor habitats are essential thanks to their support for diverse marine life, serving as critical feeding and nursery grounds, and playing a key role in maintaining the health and productivity of ocean ecosystems.

The National Wildlife Federation takes a multi-step approach to protect these habitats through careful, science-based planning to avoid, minimize, and mitigate impacts, and through monitoring and data collection.

We recommend avoiding development in high risk areas known to contain sensitive seafloor habitats, particularly complex habitats like coral reefs, which support immense biodiversity and productivity. We often ask that certain areas be avoided or taken under special consideration during the site selection process.

For example, in our Central Atlantic Call comments, we asked that the Frank R. Lautenberg Deep-Sea Coral Protection Area be removed from further consideration by BOEM to ensure protection of critical and sensitive habitat illustrated in the figure above.

In our comments to BOEM for the waters off North Carolina, we requested avoiding the Point and Diamond Shoal off the coast as an important ecological connectivity area. Designated by the South Atlantic Fisheries Management Council as a Habitat Area of Particular Concern (HAPC), this area is where the Gulf Stream, Virginia Current, and West Boundary Undercurrent converge, acting as an important migratory corridor for underwater species.

We also recommend that BOEM require detailed, site-specific research, including high-resolution seafloor mapping and habitat surveys to identify sensitive habitat features within lease areas prior to offshore wind development. This mapping will also help later in the process to minimize wildlife impacts during cable laying and the installation of turbine foundations.

This mapping and monitoring should evaluate both direct effects to seafloor habitats and indirect impacts such as sediment plumes and underwater noise, with clear, enforceable mitigation measures in place to prevent impacts to wildlife and habitats.

Where offshore wind projects move forward, they should be carefully planned to limit disturbance to the seafloor. This means choosing the exact spots for cables, anchors, and turbine foundations to avoid sensitive areas like rocky reefs, coral, and deep-sea habitats. Anchoring plans should be required, clear, and public, aiming to keep the impacted area as small as possible. No equipment should touch the seafloor in especially fragile places and there should be buffer zones to protect particularly at-risk areas from harm.

Creating Habitat

Habitat loss is a real and present danger to countless species, including horseshoe crabs. In addition to numerous other public health, economic, and environmental benefits, offshore wind sites can also create offshore habitats.

By incorporating nature-inclusive designs to turbine foundations such as textured surfaces, crevices, and artificial reefs, projects may be able to provide shelter, feeding grounds, and nursery habitat for a variety of marine species. When thoughtfully designed and strategically placed, these features can help offset some of the habitat disturbances associated with offshore wind development and contribute to the broader health and productivity of marine ecosystems.

Offshore wind energy, when developed responsibly, with meaningful engagement from Tribal and coastal communities, is one of the most effective tools we have to reduce pollution and keep our air and water clean.

Offshore Wind Energy

Offshore Wind Energy